The following observations were recorded during a brief visit to the village of Bolshiu Sliva in the Republic of Belarus.

In Belarus all dwellings were traditionally heated by a large masonry oven petchka located in the kitchen and a small to medium sized masonry heater grupka usually situated in the living area. Today almost every rural home has a petchka, but only about 40% still have and use their Grubka.

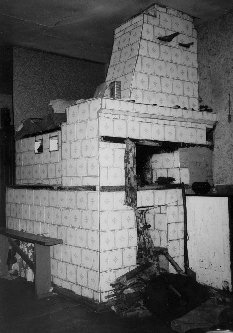

Front view of petchka built in 1978. Note the wooden step and opening to the hollow foundation behind it. The second opening to the foundation is directly below the opening in the smoke

hood. The second damper is for a briquette burning central heating furnace set at lower right. Damage to the tiled finish (middle right) was done when the furnace was plugged into the petchka.

Though less efficient than the Gruka, it is the petchka that are still built, probably due to the traditional sentimental attachement of the local population, and the multi-functional use as a heater, bed and oven. Modern homes are now built in brick, and it is said that Grubkas give out only enough heat to heat the old wooden houses. Consequently, even in some of the old wooden homes, briquette fired heating systems have replaced the Grubka.

Frontal view of a petchka built in 1976

petchka consist of a five foot long arched brick oven built on top of a hollow rectangular masonry foundation. The oven has no door, just a tin hield which is placed over the firebox opening once the fire is out.

A broad smoke hood covers the front entrance gradually tapering as it reaches the chimney connection just above the ceiling. On top of the oven, is a flat masonry sleeping platform about the size of a small double bed. This " root " used to be reserved for the oldest female member of the family.

The fire is build directly directly in the oven, its smokes and gases leaving by the only opening, which is the firebox entrance. The smoke is then drawn up into the smoke hood, where it enters the chimney.

petchka are built with clay bricks laid in clay mortar, the only other material being the iron lintels used ovet the oven and smoke hood openings, and 6" by 6" wooden beams used to span the hollow foundation.

Traditionaly finished in white, lime-based stucco , many petchkas are now given a more "up market" tile finish. The foundation is often divided into two sections, one used to store wood, and the other to keep piglets and chickens on cold nights.

The foundation is slightly larger on one side than the oven that it supports. This recess acts as a high step, which is often supplemented by a narrow wooden step closer to the floor.

Below the sleeping platform are two square openings horizontally as far as the oven's inner wall. These drying niches are often fitted with cast iron doors.

The two floor level openings in the foundation and the opening in the smoke, hood are closed off with simple curtains when the petchka is not in use.

Due to the compact layout of rural dwellings, petchka were always built against an interior wall or into an interior corner.

Traditionally in winter all cooking was done on the petchka, though now most houses have a calor-gas stove in which "fast" cooking is done.

petchka have a specific kind of cast iron cooking pot which have evolved with them. The pots are placed in the oven using a long wooden pole with two wrought iron semi-circular prongs at one end. A small pile of sand, permanently kept in the oven, is raked around the pots to speed up cooking. A long handled L-shaped rake is used to position the sand and remove the ashes.

Inside the smoke hood at either side of its opening, just above the path that the smoke takes as it leaves the oven are two cast iron shelf grills, used to smoke meat and keep a constantly warm pot of water.

Rear view of the same petchka.

Grubka are medium sized single skin Russian style masonry heaters. In rural areas they were usually built in brick with a whitewashed stucco finish. In cities, many were built with real stove stove tiles , as opposed to modern petchka which are finished in regular bathroom tiles.

Group Ka

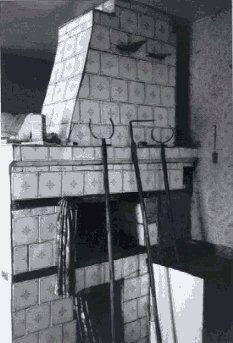

A tiled Group Ka built against an interior wall, which houses its chimney flue. Minsk was almost completely destroyed during the Second World War. Only a hand full of dwellings survived (clustered in a hollow). The house may be renovated but the heater will almost surely be demolished.

A tiled Group ka that has been virtualy destroyed by the person who removed its' cast iron doors. This image is interesting as the heater is seen free standing, though at one time it formed the juncture between two partition walls, and radiated into three seperate closed rooms. Seen here in one of the few houses in Minsk to have survived the destruction of the Great Patriotic War.

Grubka are usually free standing and located centrally in the living area.

Birch is by necessity the prefered fuel for both types of heater, with pine used as kindling. The local population is extremely conservative, with their wood supply and still practice pollarding (coppicing) . Fires are laid with great care and precision and damper adjustements during firing are frequent.

Many heaters of both types have suffered severe cracking, which the operators eagerly told me results from over firing, or firing too soon after construction.

Each village or group of villages have their own stove builder, or pichnik. The stove builders work completely from memory using no plans and having no formal training, their knowledge being passed form father to son or from master to apprentice.

Officially these pichniks are employees of the local collective farm and it is only at night or on days off that they can practice their alternative occupation.

Three of the tools used to operate the petchka. From left to right, long handled "ouchvat" used for removing the round cast iron cooking pots; right angled rake used to arrange the

sand in the oven and remove ashes; short handled "ouchvat". Not shown here is a fourth pole-like tool used to open and close the dampers which are too high to reach.

Interior view of a petchka bake chamber, showing cast iron cooking pots (Chugun or Garschok) surrounded by sand.

Traditionally it has been the local population themselves who have had to take care of their heating needs and with the central government being unable to offer a viable alternative, the individualistic behaviour of the pichnik has been reluctantly tolerated. Not only is this remarquable in such an authoritarian marxist state, but it has meant that design and building techniques have remained virtually unchanged for the last 80 years . This is in stark comparison to the North West European democracies where design and development have advanced enormously in recent years with the aid of governement and privately sponsored research and the advent of high-tech refractory materials.

In Belarus, as in the rest of the cold areas of the former Soviet Union, a heating system has evolved as a direct result of trial and error on the part of the local population over many generations.

Grubka photographed in the same dwelling as the petchka in second to top picture