It was a Saturday at about 11am, I had had a tangled knot of hair, sodium metasilicate, mask elastic, safety glasses and ear protectors on the top of my head for most of the morning, and decided it was time to take a walk in the woods.

By the side of a small pond surrounded by mature trees I came across an elderly gentleman carrying a white plastic bag.

“Bune Sur, Coshy cobo“ I said.

“Co bo“ he replied, and then said something I didn't catch. Taking a chance, I said “Co bo plo”.

He smiled.

Having exhausted my vocabulary of Occitan I introduced myself in French.

His name was Jean Talon and he said he knew who I was and why I was there. He was taking advantage of the extended mushroom season, courtesy of global warming, and showed me the two Boletus Edulis he had found. He explained that though the same species, they could be different colours and forms depending weather they were found beneath deciduous or coniferous trees.

He said that he lived two kilometers away by the bridge over the small stream. I asked if it was next to the house of the lady who made the school dinners and he said yes. “that's my daughter”.

I asked if he had an oven at home and he said of course and that most of his working life he had been a miller. The dust had got to him after several years of milling and so he had stopped and started to dress stone. Stone he said, also payed better than flour.

We said “Au revoir” and continued on our separate ways.

The following morning he came to see me, wearing his Sunday best. I asked if he was coming from mass and he inflated his cheeks saying no I don't go there. Me neither I said showing him the sponge I was holding. He laughed. I invited him in and gave him a detailed description of what I was making which did not seem to surprise to him.

He asked if I would like to come down to his hamlet, Le Mazet, to look at his oven and visit his mill.

Note: The following images were taken on two separate days.

A frosty Sunday morning seconds before sun rise in La Châtaigneraie. The hamlet of Le Mazet is out of view in the hollow 500m behind the village of Lacapelle-del-fraisse

The oven of Jean Talon. The oven itself is about 150 years old, though the bake house has been rebuilt some time in the 1950's.

The roof of the oven had also been rebuilt in the 50's at the same time as the bake house by Jean's father, using the original lauze. The roof would previously have followed the curve of the oven's facing, and had less incline and overhang

The 'eye'. This small opening traverses the facing and dome, opening into the bake chamber. As few people can remember the details of the traditional MO of these old ovens, its precise function is unclear.

The avaloir and loading opening.

The iron door of the loading opening.

Inside the bake chamber. The eye, partially blocked with cobwebs, can be seen in the centre of the 6th course.

The mill, and to the left the oven. There had always been a water powered flour mill in this location, though the original building has been extended and renovated many times, most recently by Jean and his father in the early 1950's.

View upstream.

500m upstream from the mill. Almost at the start of the leat that powered the mills turbine. The stream from which the leat draws water is out of vision, to the right,on the far side of the meadow, its course indicated by the line of low leafless bushes.

The leat, running always parallel to the stream, out of vision 20 m away and at this point 4 m lower, to the right.

This artificial channel also powered the original mill before the arrival of Jeans father. Jean estimates that it is 200 years old.

View downstream.

The reservoir and mill. Its sluice is in the far left corner. The stream at this point is 30m to the left and 6m lower than the level of the reservoir when full.

Jean indicates the position of the underground iron pipe which feeds from the sluice to to the turbine in the mills basement. One function of of the reservoir was to provide the necessary water pressure which combined with a 6m plunge, would power the turbine.

The access duct on the far side of the mill, where the water would be conveyed by a subterranean channel, back to the stream after passing through the turbine.

The Ground Floor:

'Trotters'. The feet and ankles of a wild boar have decorated the mills basement door for 40 years.

The main drive shaft from the turbine in the end wall of the mill. An electric powered motor on the other side of the wall would power the mill in times of drought.

The turbine which would have been mounted to the left of the drive shaft was removed and sold some time ago.

The iron duct, just left of the drive shaft, that fed water into the turbine.

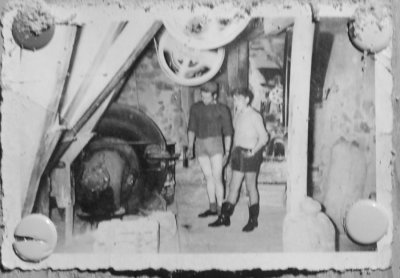

A black and white photo, taken some time in the 1950's, showing family employees looking at the turbine during operation.

The secondary drive shaft running along the basement ceiling. It is this shaft that can be seen moving in the previous black and white photo. Its wheels were the start of the power train from which the whole mill operated

The First Floor:

The three milling machines. The mechanised set up of the mill was designed by an Italian engineer, Sance, from Rodez. The carpentry ducts custom built by his German master carpenter Ebeuvid.

Two replacement rollers. The toothed rollers rotated in opposite directions at different speeds.

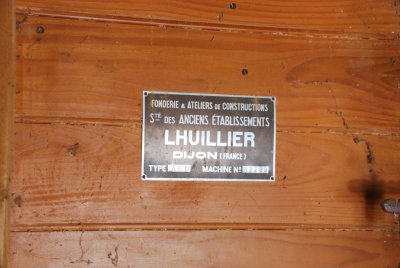

The Lhuillier 'blower' through which the grain passed before being fed through the milling machines. This apparatus would rotate the the grain in a drum through which air would be forced, driving the chaff and other contaminants through a duct in the exterior wall of the mill.

The date at which the building was extended by Jean and his father.

Canvas conveyor belts carried the ground grain through the wooden ducts to the upper floor.

The up going wooden ducts with their glass inspection windows.

The Second Floor:

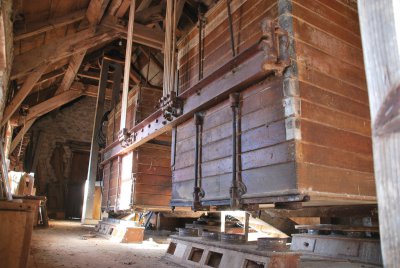

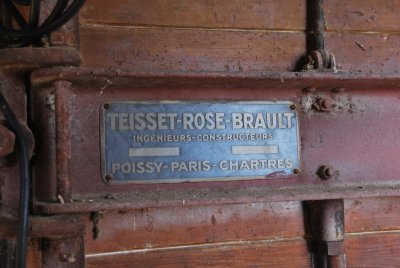

Two Tissete-Rose-Brault screens, or screening boxes. Each contains 60 individual silk screens. The flour is fed in to the top and is shaken through the screens to the bottom.

The lead counter-weight on the centrifuge between the two screening boxes. The two boxes are attached to a common chassis suspended from the ceiling by cables, When the axle is spun the weight causes the chassis to vibrate and the flour to be shaken across the screens.

Brushes that were attached to a guide ran between the two sections of silk in each screen, constantly cleaning the surface of the screens.

The feed conduits from the first floor to the top of the screening boxes.

The out ducts from the bottom of the screening boxes back to the first floor.

Both in and out ducts were attached to the moving screen boxes with sections of canvas sock attached to the ducts with wire rings.

The dispensing chutes where the flour sacks would be filled.

The loading bay up to which the mill's two trucks would back up. The 101kg bags of flour would be slid down a steel chute from the bay to the flat of the truck.

The scale used to weigh the flour bags.

The jute bags used to transport the flour weighed 1kg and so the actual bags of flour weighed 101kg.

The stencil used to mark the mill's name on its flour sacks which would be recuperated on the following delivery.

The hand seal and steel badges used to staple the tickets to the corner of the flour bags. A white ticket would indicate wheat, a red ticket rye.

Price list by the loading bay.

It was with this dynamo that the mill when running from water could work at night with all its electric lights lit. Though the surrounding villages had no electricity at the time.

After stopping milling Jean Talon spent some years dressing stone and raising trout.

Long since retired, he still spends time in the woods gathering mushrooms and hunting mammals and birds.