Traditional Exterior Bread Ovens on the Azuero Peninsula. Panama Central America (Field notes)

The largely deforested and agriculturally ravaged Azuero peninsula was colonised shortly after the conquest, and its strong indigenous population mestizied within a short time. Today the peninsula's rural inhabitants live in a network of small, evenly dispersed settlements, whose layout, and adobe dwellings closely resemble those of medieval Spain.

The following photographs and notes were taken in four villages lying on a northwesterly line roughly parallel to, and approximately 5 km from the coast, in the province of Los Santos. The distance from the northernmost village, La Laguna, to the southernmost, Pedasi, is 17 km. The sources were elderly inhabitants of the region and owner-operators of the ovens, their names being recorded only when given voluntarily. Due to the coincidental nature of my observations, conflicting information and linguistic difficulties, discrepancies to these notes are inevitable.

Pedasi

Fifty years ago Pedasi had five exterior wood-fired ovens in daily use. Today most of the bread consumed in the village is transported from the capital where it is baked in electric ovens at commercial bakeries. There is though one exterior oven in regular use, its operator selling his bread and cakes in competition with the "long life" bread baked in the national and provincial capitals.

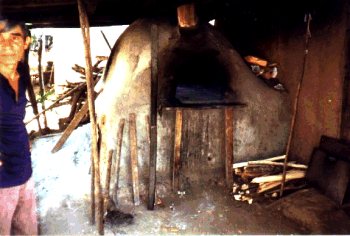

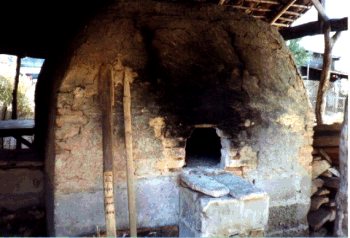

Pedasi's only oven. The stovepipe chimney connected to the dome (just above the loading door) transfers most of the smoke to the outside of the weather canopy. The oven would function just as well without chimney. The wood load at bottom right consists of long thinly split pieces, cut to encourage a fast and vigorous combustion. Note the two tin shields used to close the loading door and eye during baking.

The oven's eye and ash pile. The function of the eye is to allow the fire to draw and to regulate the temperature of the bake chamber. Once the combustion is at the ember stage, the ashes and coals are raked across the hearth towards the eye. The clear area of the hearth is then mopped, the bake load inserted and the shields placed over the loading opening and eye. The piece of wood leaning (at right) against the oven serves as a prop to keep the eye's shield in place. The eye can be opened during baking to cause a vigorous draw through the bake chamber. This relieves the bake chamber of excess heat, and avoids burning of the bake load. To increase the temperature wood can be added to the ember pile through the eye (even during baking). Both this oven and the Purio ovens have relatively large eyes, being about two-thirds the size of their loading openings. The smaller ovens of Mariabe and La Laguna have small round eyes of approximately three inches in diameter, the sole function of which is to regulate the draw.

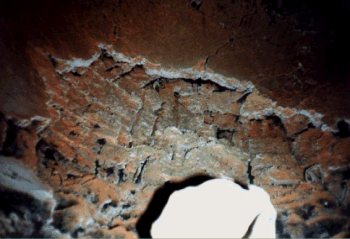

Detail of the oven's clay tiled hearth. The photograph was taken three hours after the last batch of bread was baked. The hot embers were left on the hearth close to the eye (out of view left) and both tin shields were in place. The ashes would be raked out the day after just before laying the first fire.

Interior view of the bake chamber dome showing damage to its clay parging. Built four years ago, the oven is the largest and most sophisticated of those photographed.

The baker, who, along with eighty-four year old Pedasty resident Don Moscoso, was the source of the above information.

Purio

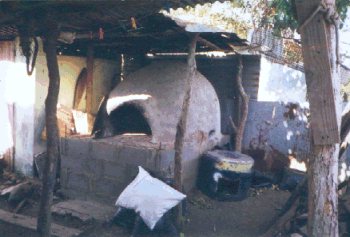

There are two ovens in Purio. The one photographed is in the back yard of its builder and operator Dona Marselina Sanchez Sanchez. Said to be "easy", it took her and her now deceased husband four days to build fourty years ago.

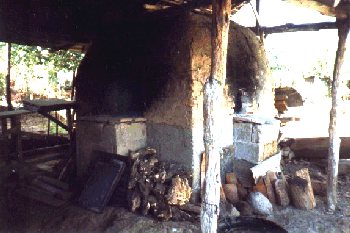

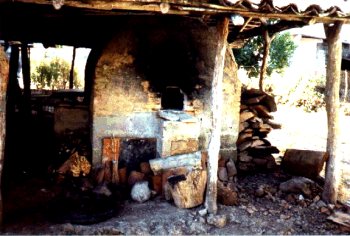

Seventy-seven year olf Dona Marselina and her oven. The villages other oven is in the back yard of the bakery across the road and is just visible to the right of the last post of Dona Marselina's oven's weather canopy. The second oven could not be inspected as on each of the occasions we entered Purio, the baker had gone to the beach.

Built upon a block foundation, this oven is unique amongst the ovens photographed in that the walls of its bake chamber are made of clay brick. The bake chamber dome though is made of clay, cast onto a wooden frame, and not of vaulted clay brick. Leaning against the foundation wall, beneath the loading opening (at left) and adjacent eye are the tin shields used to close off the two openings during baking.

The tidiness of the area around the oven and the lack of an ash pile below the eye attests to its not having been in recent use. The oven was once used to bake bread and cakes though for the last four years Dona Marselina has been incapable of baking due to a nervous disorder

Detail showing the eye and two heavily worn peels. Both the interior and exterior parging on the dome tend to flake off due to the effect of thermal shock. This oven has been re-parged several times since its construction.

Detail of the loading opening and clay tiled hearth.

Mariabe

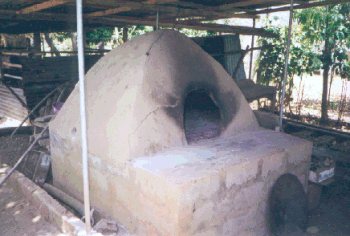

Three ovens were photographed though there are probably two others in the village. All three ovens were built by their operators and are similar in size, style and the manner in which they were constructed.

Compared with those photographed in Pedasi and Purio, Mariabe's ovens were small and primitive. They all had extremely large loading openings and small round eyes (seen here at right).

The only oven in the village parged with clay, the other two being finished in cement based exterior parging. The lines of the two main curved branches used to support the dome during its construction are clearly visible.

The least sophisticated of the ovens photographed. Note the clay hearth (not being finished in the usual clay brick or tile)

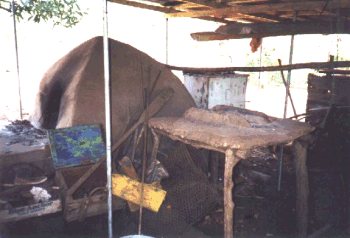

A clay parged wooden grill to the right of the oven photographed above. Note the array of baking tools leaning against the oven.

Detail of the above grill. The grill consists of an elevated wooden platform the upper surfaces of which are covered with clay. As yet I cannot say whether, like the ovens, this concept originated in medieval Spain, or whether it is indigenous to the region.

Laguna

There are no bread ovens in La Laguna though there is a "honey oven".

This apparatus is used to slowly heat up cane water (extracted from sugar cane) until it becomes syrup. Syrup is referred to as "miel de cana" (cane honey) the oven being an "orno de miel". (honey oven)

Honey ovens share the same construction principals and materials as the bread ovens of the region. As a low constant heat is required to avoid burning the syrup the clay walls of the oven provide excellent thermal storage. The syrup pan is made of aluminum, rather than steel, again to avoid burning the syrup. On the pole protruding from the pan is attached an aluminum colander (out of view) used to stir and pour the sugar water as it is heated to speed up evaporation. The loading opening is arched with a section of a forty five gallon steel drum. The eye is visible to the left of the left handle of the milk churn. The walls of this oven are built around a frame of three-inch diameter straight branches driven into the ground vertically in the form of a circle. The clay is jammed, by hand, between and around the branches that remain inside the oven's wall. As they are surrounded by clay the branches are said never to burn.

Note: For photograph and brief text describing the 'Trapiche de caña" (traditional horse powered apparatus used to extract sugar water from cane).

Additional Notes and photograph

The trapiche de caña, here being rotated in an counter-clockwise direction by two men. Normally a horse would power the trapiz. The effort is transferred to two, blunt-toothed steel rollers into which the cane is fed and crushed. The sugar water is squeezed from the cane and collected by means of a piece of galvanised guttering and a jug.

It is said that drinking large amounts of fresh sugar water will cause extreme drowsiness.

Note regarding construction. The clay used in the construction of the ovens is dug from the ground locally. In La Laguna we were shown an area of cracked dry ground said to be perfect. The 'clay' was sandy, containing ample small range aggregate, and slight vegetal contamination. Once dug from the ground, the 'clay' is placed in a mud pan and saturated with water. It is then worked into a uniform consistency by foot. Some straw is added to the clay used towards the exterior of the dome.

Note: Discrepancy. Initially I had presumed that the oven domes were made by casting the wet clay on to a dome shaped form made of pliable branches, which would eventually be burnt away by the first couple of curing fires, as is the case with the Quebecois traditional ovens. It was not until entering La Laguna (on our way out of the region) and hearing the account of the construction of the honey oven that it became evident that, at least in this case, the branch form was completely enveloped in clay and remained inside the ovens walls. At this point I cannot say whether the domes of the Pedasti, Purio and Mariabe ovens were built onto or around their branch forms. We also entered the settlements of Los Asientos, Las Cabezas, Venado and Los Pozos to the South West of Pedasi though no ovens could be found in these villages. Hopefully some of the questions raised by the information gathered here will be answered during future visits to the region.

Marcus Flynn

Montreal, May 2000