Copyright 2014 by Marcus Flynn

All Rights Reserved .

Pyromasse is Marcus Flynn ,

designer and artisan.

Though the technical knowledge and skill of the stove builder are essential, the ultimate responsibility for combustion, and overall, efficiency rests with the operator.

On Earth there is a warrior of curious origin.

He's created gleaming by two dumb creatures for the benefit of men.

Foe bears him against foe to inflict harm.

Women often fetter him, strong as he is.

If maidens and men care for him,

with due consideration and feed him frequently,

he'll faithfully obey them

and serve them well.

Men succour him for the warmth

he offers in return; but this warrior will savage

anyone who permits him to become too proud.

The Exeter Book

Copied c. 975, manuscript given to Exeter Cathedral by Bishop Leofric (died 1072)

An example of well seasoned beech.

The moisture content of the wood burnt is crucial. Wood must be seasoned, ideally for two years, and kept under cover until it contains less than 17% moisture. Moisture content is by weight, moisture accounting for 35% to 60% of the weight of freshly cut wood.

This cannot be stressed strongly enough. The difference between wet and dry wood is the difference between being cold or warm.

Wood, cut and split in early spring of 2013, that will be burned during the winter of 2014-15.

In the absence of a wood shed, covering the wood with sheets of tin held down with stones is way better than it being protected with plastic sheets.

All tree species can be used as fuel for masonry heaters. Both hard and soft wood have roughly the same calorific value weight for weight. In terms of volume approximately one third more of soft wood would need to be burnt to give the same calorific charge as a certain amount of hard wood.

Note that the rapid flare up associated with fires made from many small thin pieces of soft wood should be avoided. See following section Stacking The Fire .

Ironwood

Hickory

Oak

Sugar Maple

Beech

Yellow birch

Ash

Elm

Red Maple

Larch

White Birch

Hemlock

Poplar

Pine

Spruce

Balsam Fir

The burning of plywood, chipboard, pressure treated wood, and coloured newspaper and cardboard, should be avoided. The chemicals used in the manufacture of these products may have an unpredictable effect on the longevity of the heater, and the global environment. The ash from, in particular coloured newspaper, may contain heavy metals, and so make the whole contents of the ash dump unsuitable for spreading on gardens or making soap.

Burning of ecological logs formed from compressed sawdust is not recommended as they may burn too slowly to allow full secondary combustion.

Regular sized cord wood, that is pieces of 40 cm long and approx. 15 cm thick, is ideal. That thin pieces of split wood no larger than 10 cm. in diameter are necessary is a misconception. Small thin pieces burn faster and so are sometimes considered to intensify combustion making it more efficient. The burning of cord wood is much less intense, but still obtains near total combustion. As the fire is less vigorous, it is drawn through the smoke path at a slower rate allowing more time for captivation. Intense fires of thin wood whether hard or soft will cause more thermal shock than fires of cord wood. When it is necessary to burn thin pieces, like off cuts or dissembled pallets, they can be stacked closely together. This will restrict the movement of air through the wood load, prevent it from flaring, and make the fire last longer, as it will burn less vigorously. Images of this can be seen in the chapter Stacking The Fire .

Wood cut longer than 40 cm cannot be placed sideways in fire box making it difficult to stack a fire that will be efficient. Even when layed length ways in the fire box, logs longer than 40 cm will result in the fire being too close to the door and obstructing the primary air intake beneath the door.

It is advisable to acquire and store a wide range of wood of different thickness. The manner in which wood is stored is important. A good wood shed has a roof with large overhang, and open sides and front to allow the passage of wind. It should be located in an open sunny area rather than beneath a tree or in a shady corner.

There are two ways of stacking the fire, each a contradiction of the other.

Traditionally a 'bottom up' fire is layed with paper on the bottom, kindling on top of that and finally large wood. The flame burns vigorously up through the wood load as the fire becomes established.

The 'top down' method by comparison, places the logs on the bottom, smaller pieces upon them and kindling on top of this. The fire is lit at the top and slowly burns down through the wood load.

With the top down burn, as the fire begins to become established the flames do not pass through the wood load, causing gasses, that will not burn due to the low temperature, to be liberated and lost, as is the case with the initial stages of the bottom up burn. When lit from the top, by the time the logs begin to out-gas the gases have to pass up through a vigorous, well established fire, where they burn.

As the top down burn takes time to slowly become established, there is much less thermal shock each time the heater is fired. The top down burn will function best if the heater is set up to receive over air .

Bottom up burns are not advised as they create much more thermal shock, slightly more pollution, and are generally less efficient.

Often an operator's initial experience with the top down burn is frustrating, as if not stacked with attention the fire may go out in its initial stages. Once this is surmounted though, most operators will become top down enthusiasts.

Visual observation of both methods will make obvious the benefits of the top down burn.

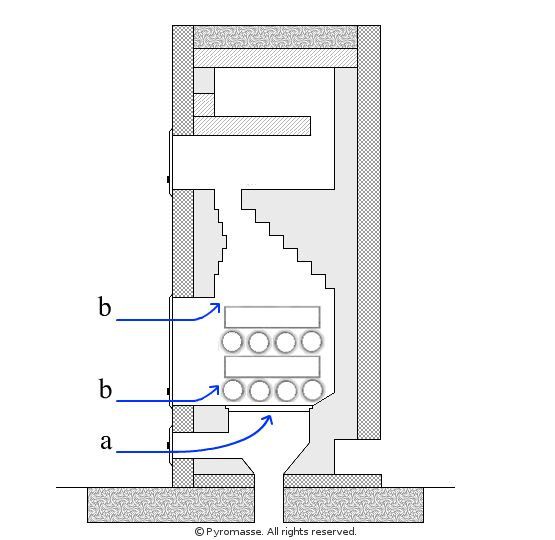

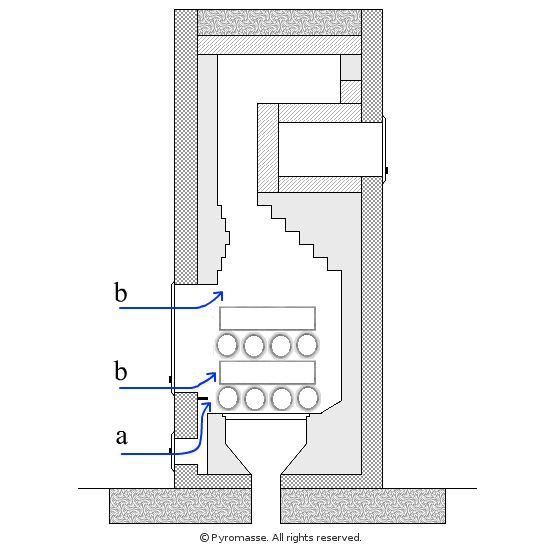

When initially introduced to North America 35 years ago the stoves built were fired with under air . This air delivery method allows air to enter below the fire box and rush up through a cast iron grate in the fire box floor. The air enters the centre of the wood load and blows flame upwards in all directions.

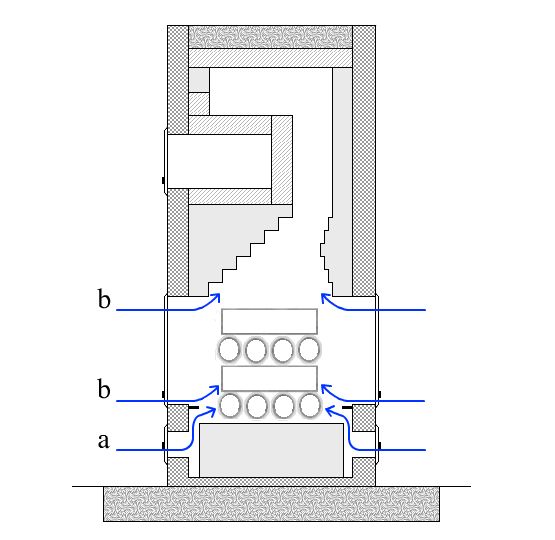

Today most masonry heaters built in North America are fired with over air. With this method no air comes through the grate which is only used to allow ash to drop and is not necessary at all.

Air enters from the primary air intake usually below the fire box door, and is drawn into the fire box, initially flowing parallel to the fire box floor. As the air is rapidly being drawn up it hits the wood load at an angle of 45 degrees to the fire box floor.

Due to the angle of delivery, over air does not cause the fire to become too vigorous, and so for reasons mentioned above, is more efficient. As air enters the fire box just below the door it blows the fire away from the door, keeping the glass clean, and the masonry around the door cooler.

Being more vigorous, under air fires amplify the effect of gas attack and Bells Reaction on the surfaces of the fire box. Excessively hot flame containing chemicals from the wood, and combustion process, particularly carbon monoxide, are blown at high velocity onto a concentrated area of the surfaces of the fire box walls around the wood load. Over air fires are far less destructive as the flames are generally less concentrated and vigorous. Most of the chemicals from the wood, and carbon monoxide, rise with the burning flame up out of the fire box where they are diluted and at lower temperature.

Primary air feeds the primary combustion of the wood load in the fire box. It enters the fire box by an adjustable primary air intake damper usually located in the facing below the fire box door.

Secondary air is intended to assure that secondary combustion, which occurs directly above the wood load, is not starved of oxygen in the event that primary combustion were to consume most of the oxygen in the primary air. Secondary air enters the fire box usually by two draft slides in the fire box door. It largely bypasses primary combustion and is mixed and burnt in secondary combustion immediately above the wood load.

Outside air: Outside combustion air is used only when code makes it obligatory. Many heaters draw air from the living area without problem.

To stack the fire, a row of the thickest logs, is placed sideways, i.e. adjacent to the grate, in the bottom of the fire box. These pieces will rest upon the sloped floor of the fire box and allow primary air to pass beneath them into the wood load. A second row of thick pieces is then layed length ways, i.e. adjacent to the first row. Space should be left between each piece in order to allow the passage of air through the wood load. The intention is to create a 40 cm square crib as far away from the door as possible. More wood can be added to the crib always layed the opposite way to the row below. Medium sized wood can be added after 3 rows of thick logs, and onto the medium wood, smaller wood. Finally, screwed up balls of newspaper can be layed on top of the crib, and kindling on top of that. If wood is stacked too tightly there will not be room for air to penetrate the wood load, and combustion may be too slow.

When lit the fire will readily progress down through the different thicknesses of wood. As the wood is cut to 40 cm and the fire box 45 cm wide, there is space each side of the crib to allow the passage of flame. There should also be a small space between the crib and the rear wall of the fire box, i.e. the wood load not stacked against the rear wall.

Firing a stove with pieces longer than 40 cm, all stacked length ways in the fire box is considered a bad practice.

As softwood burns much faster than hard wood it should be treated with a certain amount of caution when burnt on a masonry heater. Sudden flare ups of flame from a softwood fire will cause unnecessary thermal shock particularly if lighting the stove from cold.

For this reason soft wood should be stacked quite tightly in comparison to hard wood especially when burning small pieces. If stacked tightly even small pieces of softwood will burn slowly enough and not flare suddenly. The problems associated with the wood load being too tightly packed, mentioned in the paragraph above, are not applicable to soft wood.

The basic object of each fire is to burn a small quantity of wood rapidly, and then to close the damper as soon as possible.

To light the fire, the shut off damper in the chimney - and the primary air intake below the fire box door, are fully opened. This will allow a draw through the smoke path . The shut off damper and draft slide on the primary air intake, can both control the velocity of the flow, one being at the start, and one at virtually the end of the smoke path. Opening the smoke path 10 or 15 minutes before lighting the fire will allow thermosiphoning and preheat slightly the flu with temperate air drawn from the house.

The fire should be lit at the top and the door closed. All draft slides in the fire box door should be open. This will introduce secondary air that at this point will feed the small fire at the top of the crib.

As the fire becomes established the embers will fall onto, and through, the medium sized pieces igniting them. Gradually as the medium pieces burn the larger logs at the bottom will light and start to burn vigorously. From lighting to complete immolation takes about a half, to three quarters, of an hour.

When the fire is burning the chimney shut off damper should remain fully open along with both primary and secondary air intakes. At this point, when all the wood is on fire, the secondary air, feeds the secondary combustion just above the wood load.

The primary air draft slide may be closed or opened in accordance with the amount of air needed.

A vigorous fire is desired with a light flame. If the fire is obtaining full combustion, and more primary air is introduced, the fire will burn more vigorously and appear to be more efficient. As the combustion was already total, the extra air will barely affect combustion efficiency, and the added velocity will give less time for absorption and so lower overall efficiency.

On lighting the fire, the inner surfaces of the fire box and its corbelled ceiling should be white from the last fire. As a new fire becomes established, smoke will be deposited onto the relatively cool surfaces of the material turning them black. At this stage the fire is usually not hot enough to burn the smoke.

When the fire is burning vigorously and the materials reach a temperature of 600 °C all the black deposits will burn off and the surfaces of the fire box will look white. This will start to occur first on the corners of the brick in the corbelled fire box ceiling. By the end of the fire the entire fire box should be white and free of carbon deposits.

Once the wood load has turned almost to embers, but is still in place, i.e. not fallen in, the secondary air draft slides in the door can be closed. At this point most of the smoke has burned and secondary air becomes superfluous.

There will always be some primary air that makes its way through, or past, the primary combustion to feed the flame above.

If the surfaces of the fire box are not white after the fire, then it may be that something is being done wrong. Often though this occurs when small or medium fires are lit, when the heater is relatively cool. The fire is not large enough to ‘whiten off’ all or any of the surfaces.

The fire box loading doors should not be opened during combustion. And the fire never reloaded with additional wood.

The in-rush of cold air when the fire box door is opened during combustion is as detrimental in terms of thermal shock as a sudden temperature jump. Opening the door during combustion will, even when done with care, cause smoke spillage and gradual staining of the masonry above the door.

Direct or 'black' ovens should never be opened during combustion for the same reasons.

Wood should never be added to the fire once it has been lit.

Most masonry heaters are fitted with a shut off damper, usually located in the chimney. The function of the damper is to regulate the draw, and to close the smoke path to prevent thermosiphoning of heat through the smoke path. Most dampers permit fine adjustment.

As the fire begins to die down and enter the ember stage, there are two ways of proceeding. Once there is no more flame and only embers in the fire box, having the damper open will siphon off more of the accumulated heat from the stove than the embers will offer for absorption. This heat loss through the open damper represents a considerable loss in overall efficiency.

The shut off damper and primary air draft slide can be fully opened to burn the embers out fast. This will evacuate considerable heat from the mass as the flue is wide open, but only for a short time.

Or, the damper and the primary air draft slide can be closed in increments in coordination with the diminishing ember pile. This will prevent heat loss through excessive draw, but will prolong the fire as it restricts draft and draw. Both methods have the same result.

Most shut off dampers have a 5 % safety cut out that allows a continuous thermosiphon through the system, even when the damper is closed. This permits evacuation of gases from unburned embers.

The shut off damper should not be fully closed when there are visible embers in the fire box. This will cause CO AND CO 2 to spill into the living area. It is advisable that all homes be fitted with a CO and CO 2 detector.

Once all the embers are burned the shut off damper and all the draft slides can be fully closed.

If the damper is inadvertently left open for several hours the heater could loose its entire thermal charge. Heat loss through the damper is significant.

See-through is the term used to describe a masonry heater with a fire box door on both front and rear face.

Below each fire box door is a primary air intake damper. During the fire primary air is drawn from these intakes and secondary air through both doors. As it is difficult to stack a perfectly symmetrical fire, the air intakes on both faces should be adjusted to balance the fire and avoid the flame being blown towards one door.

Observing the fire during combustion will help create a bond between the stove and operator. Much can be learnt about wood and the way it burns. The experienced operator can see that the fire is burning efficiently. It is by observing the fire that subsequent fires can be stacked and lit in an appropriate manner.

The glass should be kept clean, being cleaned, if necessary, between each fire. The glass can be cleaned with a piece of damp newspaper or paper towel. Heaters that are fired with over air blow the smoke and flame away from the glass. The top down burn produces no swirling smoke in the fire box during lighting, also helping keep the glass clean.

Employing a top down burn, through well stacked fires, on a stove that uses over air, can keep the glass clean for weeks.

If firing from cold it is strongly recommended to light a small fire and let it burn out before stacking and lighting a medium sized fire. Once up to operating temperature a large fire may be lit. This procedure limits thermal shock.

When lighting from cold it takes about a day before the stove reaches operating temperature and is stabilised. It takes much longer for the structure of the house and objects within it to take on a thermal charge. For this reason masonry heaters are not well suited to chalets or cottages where the owners will only be present intermittently.

The relationship between the thermal charge of the building and that of the heater is important.

Ideally the heater should be used continuously through winter.

In cold weather two large fires at opposite ends of the day may be necessary. In milder weather one fire may suffice. In the shoulder seasons often one medium sized fire will heat for two days.

When having two fires in the same day at least six hours must be left between fires.

The concept of having three fires per day is unfounded. If there is need for this, then the stove is under sized for the space to be heated. Having three fires will waste wood and stress the stove for limited return. Heat loss through the damper is considerable. The damper would be open for most of the day and the operator obliged to be at hand.

Heaters should never be fired in summer for the sake of having a fire, or seeing fire. This is against all the ethics of wood conservation and masonry heating, and is often the selfish action of the individualist.

When firing a newly installed masonry heater for the first time it is necessary to light a series of small curing fires . Three small fires the first day, and then three larger fires the next day, before lighting a relatively big fire on the third day.

Water is gradually evacuated through the natural porosity of the material. The objective is to bring the temperature up in stages over a certain time. Lighting a large fire without having had curing fires may cause the water in the material to turn to steam and have a mechanical action on the surface of the material as it tries to escape.

If a stove is lit for the first time in autumn it may well be on a damp day with little pressure difference between inside and outside the home. As the mass of the stove will be cold it may be difficult to establish a draw. In this case the stove should be lit during early morning when the outside air will be cold, and the air inside the house slightly warmer.

Alternatively the chimney flue can be preheated with a propane torch.

The above situations are relatively rare.

Many masonry heaters have an upper chamber bake oven, which may be direct (black) or indirect (white) . These are auxiliary ovens which are heated coincidentally by the heat from the fire.

The heater should never be lit to bake in the oven, nor fired hard when meteorologic temperatures do not demand it, in order to bake.

The ovens temperatures will vary greatly depending upon the size of the last fire, and the time since the last fire. This means that it often takes a certain patience and application to become able to use the oven effectively.

The draft slide in the oven door is not of relevance and should be kept closed, particularly with a direct oven.

Though the chimney will be relatively clean it is advisable to have a chimney sweep inspect the chimney top and sweep the flue periodically.

There is no reason to have a chimney sweep clean or inspect a masonry heater.

All that needs to be done can be done by the operator.

At the base of the chimney and each side channel are 12 cm x 12 cm cast iron access doors. These allow cleaning of fly ash from the side and rear manifolds. Fly ash though accumulating here will be self regulating and only accumulate to a certain point before being swept away by the draw. The access doors also permit inspection of the manifolds and chimney connection. If necessary fly ash can be removed from the manifolds with a vacuum cleaner.

If used correctly the side channels will remain clean. Any carbon deposits on the inner surfaces of the channels, from the start of combustion will burn off as the fire's temperature rises. Cleaning the channels with a wire brush may destroy the fragile ceramic wool gasket between the channel wall and the core, and so should not be done, except in exceptional circumstances.

Instances of blocked side channels in contraflow stoves that are fired with dry hard wood, are unknown. However stoves that burn exclusively soft wood, and in particular certain types of pine, may have fly ash sticking to and gradually accumulating on the inner surfaces of the smoke path. This eventually slows down the draw, which encourages further accumulation and eventual blockage. In these cases the side channels must be cleaned with either a flexible brush or a vacuum cleaner. The lower portions of the channels can be accessed via the manifold access doors, and the upper portions, plus the area above the oven, can be accessed via the fire box.

Cleaning of the channels should only be done if nessesary and not as a routine procedure. Even in extreme cases the channels would have to be cleaned only once every two or three years.

Most heaters have some form of primary air deflector in the fire box, just below the loading doors.

The primary air channel beneath the deflector, or deflectors, should be inspected regularly as it has a tendency to become blocked with ash. The refractory brick deflectors are layed dry and can be removed to facilitate inspection and cleaning.

Note: Without the deflectors in place the primary air will bypass the wood load and the fire will not burn when lit.

If fitted with a guillotine damper, the plate should be scraped or sanded each season to remove deposits that may cause the damper to jam during summer when it is not used.

If the heater rests upon an elevated masonry foundation, ash will probably drop through the grate in the fire box floor, into the void of the foundation. It can be emptied annually.

Stoves built upon a slab, i.e. no elevated foundation, may have a grate that allows ash to drop into a tray, which is removed from the ash box door in the facing of the heater.

With this set up it is important not to let ash accumulate to the height of the grate. If there is no free space beneath the grate, then the grate may overheat and burn out prematurely, due to the insulation effect of the ash

Stoves without grate need ashes to be removed directly from the fire box floor before stacking each fire.

Wood should not be stacked against a masonry heater under any circumstances.

Loading the fire box after one fire has gone out, several hours before the next fire, is a dubious practice. Several instances of the wood load igniting, with the operators absent, have been reported.

If the wood is well seasoned and stored there is no need to pre-dry it in this manner.

All homes should be equipped with a CO and CO 2 detector.

*

The images below show a cloud of smoke igniting two feet above the wood load.

In this freak case the stove is already quite hot and a fire of soft wood lit from the bottom. Out-gassed smoke swirls around the fire box and then does, or does not ignite, depending on whether it mixes with secondary air. Normally with a bottom up fire the gases burning here will not ignite and so be wasted.

When the fire box fills with smoke during lighting it is usually due to the fire being lit from the bottom, or the primary air intake opening into the fire box being obscured by the wood load. This will not happen with a top down burn.

*

A-Z Index

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

M

N

O

P

Q

R

S

T

U

V

W

X

Y

Z

Air Set Refractory Mortar

- Refractory mortar that begins to set on contact with air.

Aluminium oxide

Alumina

- Al

2

O

3

is an amphoteric oxide of aluminium,with a high melting point. Extremely abrasive at 9 on the Mohs scale. It is derived from Bauxite. Corundum is crystalline aluminium oxide.

As a general rule, the higher the percentage of aluminium oxide in a refractory brick, the higher its temperature rating.

Bag Walls - The side walls of the secondary combustion chamber over which flow the gases as they leave the chamber and enter the side channels.

Ball Clay - Fine grained plastic sedimentary clay rich in Kaolin Extracted in cubes that became rounded during transport to the surface.Relatively scarce, deposits are found in England and NE USA. First used in modern times for making tobacco pipes in the mid17th century.

Bottom Up Burn - Name used to describe the traditional fire laying technique in which the paper and kindling are layed first followed by the medium and then large wood. The fire is lit from bellow and burns vigorously upwards.

Bypass Channel - A mechanical device used to divert the flue gases from the heater directly into the chimney. Usually located between the secondary combustion chamber and the chimney, or between a manifold and chimney when used to bypass a bench. The principle function of a bypass is to establish a draw before engaging a portion of extended smoke path.

Capping Slab - The castable refractory slab or slabs which close the top of the refractory core.

Castable Refractory Concrete - Heat resistant concrete that can be pre-cast to form modules to be used in the construction of a refractory core.

Ceramic wool

Ceramic Blanket

- High temperature woven ceramic fibre blanket, used as an expansion and smoke gasket

Chimney Cap - Cap, usually in concrete used to close the chimney top around the tile, and to protect the masonry of the chimney top from weather.

Chimney connection - The point at which the heaters smoke path is connected to its chimney.

Chimney hat - Installed over the flue tile on the chimney top to prevent rain falling directly into the flue.

Chimney Shut off Damper - A mechanical device, located in the chimney, used to close the smoke path after combustion. Also used to control the combustion by restricting the smoke path.

Chimney top damper - A chimney cap that also acts as a shut off damper, closing the smoke path on the chimney top. Usually operated by cable from inside the dwelling.

Clay Mortar - Mortar used specifically in stove and oven building. Typical mix is one fatty clay to 3 sand.

Combustion Efficiency - The efficiency of both primary and secondary combustion. Not the efficiency of any one appliance.

Common Mortar

Type N Mortar

- The mortar generally used for the laying of a heaters facade and masonry chimney.

1 Portland Cement: 1 lime: 6 sand

Corbel - A course of masonry that is layed off plumb from the course below.

Corbelled arch

False arch

- A way of closing a narrow opening by corbelling in from each side until the two corbelled portions of wall meet and support each other.

Curing Fires - A series of small fires lit immediately after the heater has been completed. These fires, gradually increasing in size are intended to dry the heater slowly, thus avoiding trapped water having a mechanical action on the materials.

Direct Oven

Black Oven

- Upper chamber oven having its bake chamber as part of the smoke path. Secondary combustion taking place within the bake chamber.

Double Bell - Russian masonry heater based upon chambers rather than channels. Developed in the late 1920s by S. J. Podgoridnikov, and introduced to North America this century by A Chernov.

Down Draught - The name given to a masonry stove which is connected to its chimney at the bottom, i.e. floor level.

Expansion Gasket

Expansion Joint

- Gasket usually, but not necessarily, of fireproof material,placed between two materials with a different expansion coefficient. Or two similar materials, with a different expansion rate against time.

Facing

Facade

Wrap

- A single wythe masonry skin, enclosing a refractory core providing the heater's double skin. It can consist of any standard dense masonry material.

Finnish Fire place

Takka

- Finnish form contraflow masonry heater.

Finnish style cookstove

Masonry cook stove

- Masonry cook stove typical of those used in Finland and Scandinavia. Achieving only partial secondary combustion, a masonry cookstove is completely independent of a masonry heater.

Fire Box

Primary Combustion Chamber

- Chamber in which the fire is layed, and in which primary combustion takes place. Accessed by the fire box loading door.

Fire Tube - Area of the core directly above the fire box where secondary combustion takes place. Found in cores with an undefined throat and upper chamber. Unlike the upper chamber the fire tube does not rely upon compression and expansion of the gases to promote secondary combustion.

Flue tile - Lining tile inserted into a section of masonry chimney to make the chimney double skinned.

Fly Ash - Fine particles of ash that are drawn through the smoke path,often accumulating on its horizontal surfaces.

Free Floating - A module that is not physically held in place by mortar, is said to be free floating.

Free Silica

Suspended Crystalline Silica

- Fine crystals of silica suspended in the atmosphere in the form of dust. Caused by the working of silica containing products. A general and specific safety hazard for the Mason.

Glorias Castillianas - The Castillian hypercauset. Still used in areas of Castille and Segovia today.

Grog

Fire sand

- A raw refractory material, high in silica and alumina. Having a relatively coarse particle range, grog is usually light and porous.

Groundoffen

Kachelofen

- Local name for the German version of the masonry heater. Built by an Hafner or Ofensetzer.

The groundofen is distinguished by its lack of grate, and it usually being built directly onto the floor .

Hair-lining - Barely visible cracks in masonry, no thicker than a human hair.

Hand Built Refractory Core

Custom built core

- Site built refractory core. Usually built by a qualified specialist entirely from refractory brick.

Heat exchange channels

Side channels

- The heat exchange channels that run down each side of the core, separated from the core by a heat resistant gasket.

Heat set refractory mortar - Refractory mortar that sets only on contact with heat. Less common than Air Set Mortar.

Heated Bench

Transmission tunnel

- Portion of extended, horizontal, smoke path deviating from the heater, before re-joining the chimney.

High Temperature Cement HTC

Refractory Mortar

- The pre-mixed 'wet' mortar used to lay refractory brick.

Hypocaust - The name given by the Romans to their system of heating bathrooms by running flue gases through a series of masonry heat exchange channels, usually in a floor. Though never or rarely achieving secondary combustion these heating systems are considered to be the first recorded examples of the deliberate use of thermal retention within masonry mass. Evidence of their use can be found throughout the former Roman world.

Indirect Oven

White Oven

- Oven located in the upper chamber but being entirely closed to the smoke path. Secondary combustion takes place below, above, behind, and to the sides of the bake chamber.

J –Loop - An adaption of a contraflow stove where the gases descend one side channel, and return up through the other side channel before exiting at the top of the stove. As opposed to the gases descending both side channels and exiting at the bottom.

Kakelugn - Local name for the Swedish version of the Masonry Heater.

Kamen - Local Word used in many eastern languages. Sometimes used to describe a masonry stove, but more often a traditional masonry fire place, or chimney.

Klang - Manchurian version of the Ondol.

Lime Mortar - Mortar used for general masonry work until the beginning of the 20th century. Usually 1 portion of lime to 3 of sand.

Lintel - A horizontal beam used to traverse an opening. Can be of stone, iron, refractory concrete, or common concrete.

Load Relieving Lintel - A lintel used to transfer compressive force, away from potential week point.

Manifold - The widened area of the smoke path directly beneath each side channel. There are three manifolds in a contraflow core; left and right side manifolds and a rear manifold running beneath the back portions of the fire box, which connects the two side manifolds.

Mechanical bridge - A solid contact between two otherwise separate, rigid materials,causing the possibility of one having a mechanical action on the other due to thermal expansion.

Ondol - Korean domestic version of the hypocaust having the form of a ceramic sitting or sleeping platform. The Ondol is still used in Korea today, though most are fired with oil or gas.

Over Air - The name given to the method of delivery for primary combustion air, in which it is directed onto the wood load either laterally or from above. The distinction being that no air rises through a grate beneath the wood load.

Piets - Local name of the Polish version of the masonry heater. Built by the Dzrune

Pichka - Russian name for the Russian domestic masonry oven. Built by a Pich Nik

Prefabricated Masonry Heater - Heater completely prefabricated, i.e. core and facing.

Prefabricated Refractory Core

Pre-Fab Kit

- Refractory core that is entirely factory made, consisting usually of castable refractory concrete modules. Can be installed by nonspecialised mason.

Primary Combustion Air - Air drawn in to the fire box, usually from an intake in the facing below the fire box door, which feeds the primary combustion of the wood load. Primary air makes up most of the flow in the smoke path.

Priming fires - The small fire lit when the heater is being used from a cold start. These fires bring the heater slowly up to operating temperature, avoiding thermal shock.

Refractory core - The interior portions of a masonry heater, which enclose the smoke path. Usually, though not necessarily, made from refractory brick or concrete.

Russian Stove

- A general name user to describe stoves built throughout the former soviet empire. Built by a Pechnik.

Local names include petch, pich, grubca, gruba.

Secondary Combustion.

Double Combustion

- Ignition and combustion of unburned gases, during, and immediately after primary combustion.

Secondary Combustion Air - Air drawn into the fire box, usually through an intake in the fire box door. This air bypasses the primary combustion, travels across the fire box ceiling and mixes with the smoke and flame to nourish secondary combustion.

Secondary Combustion Chamber

Expansion Chamber

Upper Chamber

- Chamber above the fire box, connected to it by the throat, where secondary combustion of the flue gases takes place, before the gases flow into the side channels.

Secondary Combustion Chamber Oven

Upper Chamber Oven

- Auxiliary oven taking up space within the heaters upper chamber. Having a loading opening on the front or rear face of the heater.

See Through Heater - A heater with a firebox loading opening on both front and rear face. Generally considered to be slightly less efficient than a heater with only one fire box loading opening.

Semi prefabricated refractory core - Refractory core containing some precast modules of refractory concrete, but necessitating the laying of some fire brick during their assembly.

Shiners - Brick that are layed face down i.e. on edge, rather than bed down.

Silicosis - An incurable lung disease contracted from prolonged exposure to suspended crystalline silica. Note: In France it is said "Une bonne fumist est mort a 50 année".

Smoke gasket - Gasket of fire proof material used to inhibit the passage of smoke from one portion of the heater to an other.

Smoke Hood, Avaloire - Hood or funnel in masonry or metal, used to draw smoke together towards and into a chimney. Found on the front of direct fired ovens.

Smoke Path - The path taken by the draw of the system through itself. Beginning at the primary air intake door and ending at the top of the chimney.

Soba de Terracota - Local name for the Romanian version of the masonry heater. Built by a Sobar.

Sodium Silicate,

Water Glass

- Actual Name: Sodium meta-silicate, Na

2

SiO

3

Used as a bonder (hardener) in refractory mortars. Available in dry or liquid form.

Soot Doors

Clean Outs

- Openings giving access to the manifolds, or other portions of the smoke path. Usually fitted with cast iron doors.

Spalling - The disintegration and loss of the exposed surfaces of material.

Thermal Break - A layer of insulating material placed between two dense conductive materials with the intention of impeding thermal transmission.

Thermal Bridge - A solid bridge allowing the conduction of heat from one dense material to another.

Thermal cycling - The cyclic rise and fall in temperature which occurs during and after each fire.

Thermal Shock - The destructive action caused on a material that is brought up to temperature too fast, or unevenly. The main enemy to the longevity of the masonry heater.

Thermal Stress - The detrimental effect of a material that is saturated, accumulating heat faster than it can transfer heat, resulting in cracking and warping.

Thermosiphon - The natural tendency for hot air to rise as it is displaced by cold air.

Throat - Point at which the fire box ceiling narrows, compressing the gases. Usually precedes the upper expansion chamber.

Top Down Burn - Name used to describe the manner in which a fire is layed, with the large wood on the bottom, medium wood above that and finally the paper and kindling layed on top. The fire is lit at the top and burns slowly from the top down.

Total Efficiency - The total efficiency of the appliance, of which combustion efficiency is a part.

Transfer Efficiency - The measure of a material's capacity of thermal transfer overtime.

Under Air - The name used to describe the manner in which primary combustion air enters the fire box via a grate in the fire box floor.

Up Draught - The name given to a masonry stove which is connected to it's chimney at the top of the stove

Zdun - The Polish name for stove builder.

*

*